Accused of hypocrisy, the Biden Administration still seeks Assange's extradition from the UK to face charges of espionage in the United States. Assange presently is appealing approval by the British home secretary of the extradition request.

Having co-founded WikiLeaks in 2006, Assange long advocated for absolutism in the freedom of information. But when WikiLeaks received a trove of records from U.S. soldier Chelsea Manning, Assange did enlist the help of journalists to filter the material for public consumption in an effort to protect people, such as confidential informants whose lives would be at risk if they were named as collaborators with western forces.

Nevertheless, the subsequent publication of records in 2010 and 2011 outraged the West. The records included secret military logs and cables about U.S. involvement in Iraq and, as Al Jazeera described, "previously unreported details about civilian deaths, friendly-fire casualties, U.S. air raids, al-Qaeda’s role in [Afghanistan], and nations providing support to Afghan leaders and the Taliban." Especially damaging to western interests was a video of arguably reckless U.S. helicopter fire on Iraqis, killing two Reuters journalists.

Manning was court-martialed for the leaks. President Obama commuted her sentence in 2017.

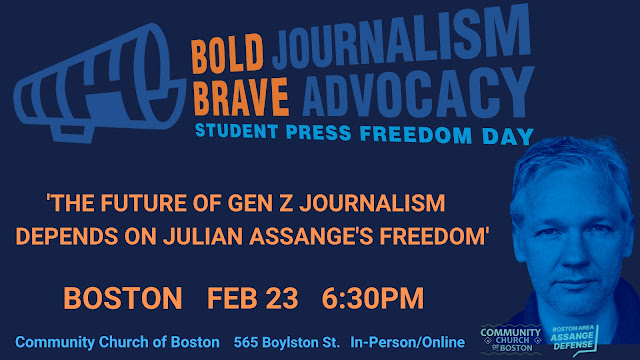

Thursday's program is titled, "The Future of Gen Z Journalism Depends on Julian Assange's Freedom." From Boston Area Assange Defense, here is the description.

Boston Area Assange Defense invites you to attend a panel discussion on how the U.S. prosecution of Julian Assange impacts the future of journalism. This event is part of the Student Press Freedom Day 2023 initiative: "Bold Journalism/Brave Advocacy."

The reality is that "Bold Journalism" has landed Julian Assange in a supermax prison for publishing the most important journalistic work of this century. Our First Amendment rights are threatened by this unconstitutional prosecution of a journalist and gives the US government global jurisdiction over journalists who publish that which embarrasses the US or exposes its crimes.

Prestigious international lawyer Prof. Nils Melzer (appointed in 2016 as UN Special Torture Rapporteur) authored, The Trial of Julian Assange, A Story of Persecution. The book is a firsthand account of having examined Assange at Belmarsh prison and having communicated with four "democratic" states about his diagnosis of Assange exhibiting signs of persecution. He wrote, "I write this book not as a lawyer for Julian Assange but as an advocate for humanity, truth, and the rule of law." "At stake is nothing less than the future of democracy. I do not intend to leave to our children a world where governments can disregard the rule of law with impunity, and where telling the truth has become a crime." Melzer stated, "If the main media organizations joined forces, I believe that this case would be over in ten days."

Boston Area Assange Defense platforms this experienced panel of journalists for a lively conversation about the Assange prosecution, its threat to journalism and the rule of law. Also, a short video clip narrated by Julian Assange's wife will be streamed for informational and discussion purposes.

Students and citizens alike are entitled to a free press so that we can make informed decisions.

A free press is the cornerstone of our democracy.

We must fight against censorship and the criminalization of journalism.

We must show "Brave Advocacy" to end the prosecution of Julian Assange!

Please join us February 23rd for this important "Bold Journalism/Brave Advocacy" event.

Students are invited so kindly share this event with your students!

Community Church of Boston's YouTube.

People will also gather at the Community Church of Boston, 565 Boylston St., near Copley Square.

An Assange information table will be set up with literature and petition to MA senators. Boston Area Assange Defense will be present to answer questions....

Guest speakers:

- Jeremy Kuzmarov, Author and Educator, Managing Editor, Covert Action Magazine

- Esther Iverem, Journalist, Producer, Radio Host, "On the Ground: Voices of Resistance from the Nation's Capital," nationally syndicated on the Pacifica Network

- Sam Carliner, Journalist; Sam's Jan. 2021 article covering the Dept of Justice DC rally during Assange's extradition hearing

- Tarang Saluja, Student, Activist, Journalist

.jpg)

.jpg)