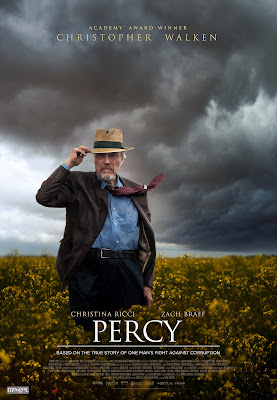

I caught up with the film last weekend. As the title suggests, it's a David vs. Goliath story about a workaday Canadian farmer, Percy Schmeiser (Walken) sued by agriculture giant Monsanto when Roundup-resistant canola strains turned up in the farmer's fields in Saskatchewan. Schmeiser countersued for libel and trespass.

The real-life case is Monsanto Canada Inc. v. Schmeiser (Can. 2004). The real-life Percy died in 2020 soon after the film was completed. There have been several documentaries about the case, besides this fictionalization.

Spoilers ahead.

Something I liked and had not expected in the film is the depiction of Percy's visit to India. The filmmakers do a good job conveying the fact that GMO seed drift and patent exclusivity is a worldwide problem. The film doesn't directly tackle the unknown risks of GMOs, both to human health and in global monoculture, but they're implicit in Percy's reasons for resisting GMO tech.

The film also doesn't tackle the separate problem of Roundup toxicity, which fueled mass tort litigation in the United States only later, in the 2010s. But the repeated mention of the product can't help but bring the issue to mind with the benefit of hindsight. (Certainly it brings the issue to my mind, remembering my summer work as a landscape laborer, Roundup streaming down my arms. Though that's nothing compared with soaked workers I saw on Central American fruit plantations in the 1990s.) Bayer acquired Monsanto in 2018 and agreed to settlements over Roundup in 2020.

Percy mostly won in the end, in that Monsanto could not prove deliberate appropriation. But the court did find patent infringement and required Percy to surrender his seeds to Monsanto.

In the United States, the Supreme Court in 2013 ruled in favor of Monsanto in a seed case with different facts, Bowman v. Monsanto Co. An Indiana farmer had replanted seeds that Monsanto clients had sold to a grain elevator in violation of Monsanto's license, which prohibited downstream reuse. The later buyer infringed the patent, the court concluded.

In a U.S. case closer to Schmeiser but with a different procedural history, a broad farming coalition sought to nullify Monsanto patents to head off infringement claims they saw as an inevitable result of genetic drift. The court rejected the suit in Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association v. Monsanto Co. (Fed. Cir. 2013) for lack of controversy. Monsanto thereafter announced that it would not pursue infringement claims against non-client farmers for Roundup-resistant strains as long as they didn't use Roundup.

Informative for comparative law class, the film, Percy, includes a short courtroom scene toward the end in which Percy's solo lawyer Jackson Weaver (Braff) argues against the Big Ag sharks in the Canadian high court. Christina Ricci turned in an enjoyable supporting performance as environmental activist lawyer Rebecca Salcau. I recall that Ricci delightfully played scrappy attorney Liza Bump in the final season of Ally McBeal.

Weaver's and Salcau's resource limitations in facing off against Big Ag brought to mind A Civil Action (1998), and Percy overall is reminiscent of Dark Waters (2019) (on this blog). Percy's quiet tribulation is not the stuff of blockbusters, but it's surely worth the watch for anyone interested in the broad range of issues it raises in environmentalism, agriculture, food supply, civil litigation, product liability, intellectual property, and corporatocracy.

Though it was not a policy point in the film, I found compelling attorney Weaver's warning to Percy that losing the case would mean not only compensation on the merits to Monsanto, but liability to Monsanto for hundreds of thousands of dollars in fees for the very Big Ag attorneys who rendered the litigation playing field so unlevel as might, circularly, precipitate the loss.

Such is the rule for attorney fees in Canada and most of the world, and, alarmingly to me, more and more, by statute, in the United States. Civil rights advocates and the plaintiff bar herald attorney-fee shifting as vital to facilitate access to the courts for injured persons. But when the burn works both ways and a corporate Goliath prevails, the result should give us pause before wholeheartedly chucking out the pay-your-own-way rule of American common law. Writ small, this precisely is one of my objections to anti-SLAPP laws that place genuinely victimized individual plaintiffs at risk of having to pay outrageous fee awards to compensate corporate mass media defense attorneys.

I watched Percy vs. Goliath on the Roku Channel with ads. The film is available for less than $4 on many streaming platforms.