On April 7, one of my favorite podcasts, WNYC's

On The Media (OTM), ran a

story, not its

first, on anti-

SLAPP laws:

statutes in the states (not yet

federal) designed to combat "strategic lawsuits against public participation."

I've written about anti-SLAPP many times. I'm not a fan of the statutes. The OTM piece is good and important, but it tells only one side of the anti-SLAPP story. That's a common, and forgivable, shortcoming in mass media coverage of itself.

Why I Care, and You Should Too

I've been a media advocate since I was hooked by my first high school journalism class in the 1980s (hat tip at Mrs. McConnell). I've been a media defense lawyer and a

defamation plaintiff, besides a classroom teacher of media law and the First Amendment. My hang-up is

justice, or the remediation of injustice (yes, I'm

a J), and there's plenty of both in the way our news media work in the shadow cast by the shield of the First Amendment. Advocating for the devil in my classroom, I was a critic of the

Sullivan/

Gertz actual malice standard decades before it became

fashionable, or even socially acceptable in academic circles,

to question the supposed sine qua non of free speech.

So when the media defense bar teamed up with state legislators to start piling on anti-SLAPP statutes as another death-blow weapon in the scorched-earth media defense arsenal in the late 1990s, I was skeptical from the get-go. Upon the siren song of free speech absolutism, now decades on, Americans have fallen into the lazy habit of denying access to our courts to would-be plaintiffs who are genuinely victimized. As a scholarly observer of tort law, I can tell you, bad things happen when people are systematically disenfranchised from justice. What's worse, as empirical research has consistently told us for decades, and I confirm from my own experience, the ordinary defamation plaintiff is not the money-grubbing opportunist that tort reformers (or distorters) wish us to imagine; rather, what a defamation plaintiff usually wants, first and foremost, is the truth. News media defendants might remember the truth from journalism school.

How did we get to a point that when a plaintiff and defendant want the same thing, it's still a zero-sum game? If with the best of intentions, the U.S. Supreme Court in the civil rights era so distorted the state landscape of defamation law that media defendants lost all interest in compromise, even if the simple compromise is to correct the record and speak the truth. Sullivan biographer Anthony Lewis recognized this problem in the penultimate chapter of his otherwise-paean to the case in 1992. And this is why the 1993 Uniform Correction or Clarification of Defamation Act proved a profound failure. The uniform law proposed using a First Amendment-compliant carrot rather than a constitutionally prohibited stick to coax media defendants to hear complainants out before facing off in court. But, media defendants implicitly pleaded in response, why should we listen when we always win?

Anti-SLAPP laws are perfect for the thing they're perfect for: To shut down an obvious attempt to abuse the legal process with a sham claim when the plaintiff's true motivation is to harass or silence a defendant engaged in constitutionally protected speech or petitioning, especially when it's whistle-blowing. "I know it when I see it" is why a South African judge recently allowed anti-SLAPP as an "abuse of process" defense even in the absence of a statute, shutting down a mining company's implausible suit against environmentalists. Meanwhile, the American anti-SLAPP statute, the darling offspring of mass media corporate conglomerates and financially beholden legislators, tears through court dockets with no regard for the balance of power between the parties.

As a result, sometimes, like the infinite monkey who stumbles onto Hamlet, anti-SLAPP works. Other times, David is summarily shut out of court at the behest of Goliath. The dirty secret of the media defense bar is that it's pulling for the latter scenario more often than the former, because Davids pose a much greater threat to the corporate bottom line than the occasional, over-hyped monkey.

Squirrel! SLAPPs Aren't the Problem

SLAPP suits only work because of a bigger dysfunction in tort law: Transaction costs are way too high. Lawyers and litigation cost too much. (Law school costs too much, but that's another rabbit hole.) Our civil dispute resolution system, in contrast with those of other countries, so prizes precision as to draw out civil proceedings to absurd expectations of time, energy, heartache, and money. Too often, at the end of a litigation, both exhausted parties are net losers, and only the lawyers, on both sides, come out ahead. The tort system is supposed to engender social norms and deter anti-social conduct through its compensation awards, not its overhead costs. We've so contorted torts, especially when accounting for suits that are never brought, that the norm-setting and deterrent effects of transaction costs dwarf the impact of outcomes.

Anti-SLAPP tries to solve the problem of runaway transaction costs by summarily dismissing claims on the merits when a plaintiff cannot prove the case at the time of filing, usually without the benefit of discovery. The game is rigged, because the evidence the plaintiff needs is in the possession of the defense. So plaintiff's unlikely path to proof, already mined with common law and constitutional obstacles to press the scale down on the defense side, is well obliterated by anti-SLAPP. We could use this "solution" of summary dismissal across the board to cut back on tort litigation. But people wouldn't stand for it in conventional personal injury, because then we'd be overrun with uncompensated and visibly afflicted plaintiffs, and the injustice would be undeniable.

If we dared have the creativity to experiment with more effective dispute resolution mechanisms as alternatives to tort litigation, we might best start with defamation cases, in which we know what plaintiffs want, and it's not money. Yet here we are, hamstrung by the Supreme Court, disenfranchised by defense lobbyists, and forced to swallow the dangerous myth that we can have free speech only if we stand aside and let mass media deliver misinformation with impunity.

The Case of the Charity Exposé

and the Lamentations of the Media Defense Bar

In the April segment, OTM host and media veteran Bob Garfield interviewed Victoria Baranetsky, general counsel for the 501(c)(3) nonprofit Center for Investigative Reporting (CIR), about a lawsuit by also-501(c)(3) nonprofit Planet Aid against CIR. The lawsuit arose from a 2016 series on the CIR Reveal platform, in which CIR alleged abuse of charitable status by the organization through, inter alia, improper diversion of donor funds. A California federal judge dismissed the 2018 complaint in March 2021, and Planet Aid, which is appealing, and CIR have very different takes on what that dismissal meant. Planet Aid emphasizes "46 statements" in the reporting that the court found false, notwithstanding anti-SLAPP dismissal, while CIR emphasizes "several million dollars" of legal costs, "vastly exceed[ing] ... insurance coverage" and impossible to pay without pro bono aid.

CIR is not an outfit that publishes without doing its homework. So without opining on the merits of the lawsuit, I admit, my gut allegiance in the case tends to CIR. And I think it's OK that OTM interviewed only Baranetsky. "Balance" as a journalistic value too often feeds the "talking heads" phenomenon we know from the disintegration of television broadcast journalism. OTM's report was about the toll of litigation on journalism, not the merits of the CIR stories. Looking, then, at the OTM story, I find that a side was missing, but it wasn't Planet Aid's. Missing is reasoned resistance to the anti-SLAPP craze. Here, then, are my reflections on five media lamentations in the OTM story about anti-SLAPP.

Lamentation Over Forum Shopping

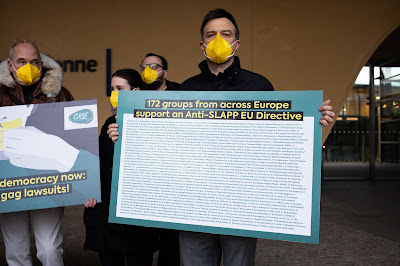

(1) Baranetsky lamented that Planet Aid was permitted to sue in Maryland, where the law was advantageous to a plaintiff, and CIR was forced to incur major costs to move the case to California, where anti-SLAPP law is more protective. Federal anti-SLAPP would fix this problem.

Forum shopping is a problem, but not specially a media defense problem. Barring defamation victims from redress equally across the states isn't better than barring them one state at a time; i.e., 50 wrongs don't make a right. Rather, everything that's wrong with anti-SLAPP would be multiplied by a federal statute. Plaintiff's choice of forum does aggravate costs, and that allows forum shopping to be used improperly as a SLAPP tool. The answer is to change how we manage forum selection in federal civil procedure to stop the externalization of costs to defendants and to compel professionalism in the plaintiffs' bar—not to put a thumb on the scale of merits in lawsuits, even SLAPPs.

Moreover, in overriding state court discretion to hear defamation actions on the merits, a federal anti-SLAPP statute would double down on the entrenched Sullivan/Gertz paralysis of the tort system that's precluding the development of innovative alternatives. Our problem in defamation law is not lack of uniformity in the states, but precisely the opposite, lack of diversity that would generate new approaches.

Lamentation Over the Burdens of Discovery

(2) Baranetsky lamented that California federal courts have allowed limited discovery before dismissing cases under California anti-SLAPP law, thereby upping the costs of money and time for media defendants and mitigating the efficacy of anti-SLAPP.

Notwithstanding the present debate in the Courts of Appeal over whether state anti-SLAPP laws can displace federal court process, anti-SLAPP puts defamation plaintiffs in a no-win scenario, especially when the plaintiff is a public figure. Under Sullivan/Gertz, a public-figure plaintiff can prevail only by proving subjective knowledge or intent on the part of the defendant to publish falsity. Subjective culpability lies only in the mind of the defendant. Without precogs, we prove subjective culpability with circumstantial evidence. When the defendant is a mass media organization, that evidence is in the possession of the defendant. Even in a negligence case with a private-figure plaintiff, it is impossible to probe the culpability of the defendant when the plaintiff has no knowledge of the defendant's internal process, even the identity of a staff editorial writer, for example.

Yet along comes anti-SLAPP to demand (in the usual formulation) that a plaintiff prove likelihood of success on the merits with evidence that the plaintiff could not possibly possess. Win-win for the media defense, lose-lose for access to justice. Baranetsky bemoaned the costs, tangible and intangible, of discovery, especially on a nonprofit media outlet. With that complaint, I am sympathetic. Again, though, the answer is to change the process to control transaction costs. The long reach of American discovery is globally infamous and socially problematic in ways well beyond the woes of media defendants.

Baranetsky raised the further point that the permitted discovery was one-sided, so CIR was not able to use discovery to bolster what might be a winning affirmative defense, such as truth. I take this point, too. I have some concern about the potential for a media organization—imagine not CIR, but a more partisan and unscrupulous outfit—to misuse discovery to further ill intentions. But courts can and should control the scope of discovery with appropriate protective orders.

Lamentation Over Interment by Paper

(3) Baranetsky lamented that the Planet Aid "complaint was about 66 pages, almost 70 pages long.... [B]ecause our reporters did such extensive reporting, published on the

radio, published online, there were a lot of remarks to pull in from a

really substantive investigation. The complaint here was padded with all

of those bells and whistles." That again upped media defense costs and slowed down the anti-SLAPP process.

I don't doubt that the complaint was longer than it needed to be. Plaintiffs anticipating high-profile litigation—by the way, including agenda-seeking litigators from both left and right, as well as state attorneys general—routinely plead "to the media" and to "the court of public opinion," rather than to the court of law. Excessive pleading runs up defense costs, as well as court time, which is not fair to litigants or taxpayers. Again, the answer lies in bar and bench control of process and professionalism, not in summary dismissal on the merits.

More importantly, to some extent, a defamation plaintiff's claim in a case over a series of reports must be lengthy, for a very reason Baranetsky said, and not because the plaintiff wants it that way. It's not "padding," "bells," or "whistles." Defamation plaintiffs are compelled by rules of pleading to commit a perverse self-injury by republishing the defamation of which they complain. Thereafter, mass media entities are permitted to restate the defamation as a fair report of a public record, almost with impunity. As a result, often, the defamation is amplified, and the plaintiff's suffering is vastly compounded. Even if the plaintiff wins the case, compensation for this added injury is disallowed, and no media entity can ever be compelled to correct or update the record by reporting that the plaintiff later prevailed upon proof of falsity.

In my own plaintiff's case, precisely this happened. Among countless national outlets, The New York Times reported the defamatory allegations I republished in the complaint, but never covered the case again, despite my entreaties to the reporter and ombudsperson. To this day, I overhear innuendo based on the Times story with no reference to my later exoneration, which was reported in only one excellent-but-niche publication. In my experience with would-be defamation plaintiffs, I have seen that this risk alone prevents a victim from seeking redress as often as not. Once again, we could answer this problem by reforming pleading in defamation, rethinking what "fair report" means in the digital age, and experimenting with dispute resolution, if only Sullivan/Gertz left the defense bar with the slightest incentive to participate.

Lamentation Over Litigiousness

(4) In his introduction to the case, Garfield said, "Without offering evidence to rebut the allegations, the charity promptly sued the news organization for libel."

OTM itself walked back this characterization of Planet Aid's lawsuit as a blindside attack. An OTM editor's note to the story posted online added that, according to a PR firm representing Planet Aid, the organization "reached out to

[CIR] prior to filing its lawsuit asking

for a retraction and correction."

I don't know whether Planet Aid's version is right, or OTM's, or maybe the demand letter got lost in the mail. As I've indicated, I'm not rushing to sign up Planet Aid as my poster child for the Anti-SLAPP Resistance. But OTM's post hoc characterization of events is, to my experience, typical of media-defense-bar spin. In reality, rare in the extreme is the case that there is not at least a demand letter and response.

In my own plaintiff's case, I filed suit as late as possible, on the eve of the expiration of the statute of limitations. I sought to diffuse the disagreement through every possible avenue, both vis-à-vis my defendants and through negotiation with a third party. Yet when my case turned up years later in a book by an academic colleague, Amy Gajda, she used my case to support the book's thesis that alternative dispute resolution mechanisms on university campuses would help to avert lawsuits by litigious academic plaintiffs like me. I don't dispute (or support) that thesis in the abstract, but my case did not support it. Gajda suggested that I rushed to sue, without probing alternatives, which was utterly false. In fact, it was the refusal of my potential defendants to come to the table—the very problem of Sullivan/Gertz inhibition of dispute resolution—that forced me into a lawsuit as an undesired last resort.

Gajda, by the way, is herself an award-winning journalist and scholar of media law. Yet she readily contorted the procedural facts of my case to fit her expectations without ever asking me what happened. We know each other, and I'm not hard to find. If a top-flight journalist can be so sloppy with the facts in a case about a professional colleague, and I have to lump it, what chance does a lay soul in private life have to correct the record on something that really matters, as against a professional media outlet with a partisan agenda and lawyers on retainer?

How simple it is to make assumptions and feed the tort reformer's myth that greedy plaintiffs eagerly sue at the drop of a hat. Yet no one properly counseled by an experienced attorney chooses a lawsuit as a first course of redress. To the contrary, defamation victims, especially in matters as difficult to win as media torts, typically cannot find an attorney willing to take the case at the opportunity cost of sure-thing personal-injury money, and certainly not on contingency. Plaintiffs wind up not suing for that or many other reasons unrelated to their real losses. Other reasons include the risk, under anti-SLAPP fee-shifting, of having to pay attorneys' fees to a corporate media defendant's high-priced lawyers—not because the plaintiff wasn't defamed, but because the plaintiff could not meet the enhanced burdens to overcome a First Amendment defense. Other reasons also include the stigma associated with being a plaintiff in America, a stigma perpetrated by corporate advocates of tort reform and conveniently perpetuated by would-rather-not-be defendants in the media business.

Lamentation Over the Price of Free Speech

(5) Baranetsky opined, "We have to be wary of defamation law being used by public figures and

politicians and wielded in ways that can be used retributively. At the

same time, make sure that lies aren't being spread. The hope is that anti-SLAPP laws are really, they're the precise scalpel

that's supposed to sharply and acutely figure out which falls on which

side of the line."

That's a profound misapprehension of anti-SLAPP laws. There is nothing about anti-SLAPP that is precise or acute. Very much to the contrary, anti-SLAPP is designed to be a blunt instrument that stomps out litigation before it can get started, looking scarcely at the quantum of evidence on the merits and rounding down in favor of the defense. Anti-SLAPP operates upon the very theory of Sullivan/Gertz, which is that the price of free speech is the prophylactic annulment of meritorious claims and the tolerance of misinformation. The theory of anti-SLAPP is that we don't want to know the truth, and would rather abide falsity, when the cost of disentangling truth and falsity is inconveniently excessive.

Baranetsky's take on anti-SLAPP is ironic in the extreme. The Sullivan/Gertz constitutionalization of state tort law is based on the age-old argumentative hypothesis of moral philosophy that "the truth will out" in the marketplace of ideas, so the courts ought not intervene to abate falsity. That proposition has been vigorously refuted by scholars as demonstrably erroneous. And CIR's very motto, splashed on a home page banner, is: "The truth will not reveal itself."

𓀋

I've identified areas of tort law that need reform—abuse of forum selection, excessively broad discovery, permissiveness of fact pleading—and areas of defamation law in particular that need reform, procedural and substantive—pleading requirements, fair report protection, culpability and proof standards, plaintiff access to representation, and availability of alternative dispute resolution—but are paralyzed by federal capture of common law and media defense intransigence.

Let me not understate my appreciation for OTM, WNYC, CIR, and all kinds of nonprofit journalistic enterprises. I am grateful that CIR did the reporting that it did on Planet Aid, and for the reporting that OTM does all the time on threats to public interest journalism. I am fearful of a world in which that reporting does not happen.

Nevertheless, I object to a legal standard that presumes news media have the corner market on truth. If our system of civil dispute resolution is broken, and I think it is, then we need to fix it. Anti-SLAPP is at best a patch to paper over unsightly symptoms of our dysfunction, and, too often, it does so at the expense of genuine victims. Our willingness to ignore injury says more about the sorry state of our democratic character than does our blind fealty to an unbridled press.

At the annual meeting earlier this year of the Communications Law Forum of the American Bar Association, a famously media defense-identifying conference, I heard whispered for the first time some cautious and reluctant concern that media defendants holding all the cards in tort litigation might—wait, is this a secure channel?—might not necessarily be the best strategy to ensure the freedom of speech and to protect the flow of truthful information in America, especially in the digital age.

Now where have I heard that before?