|

| Columbus is absent from Government House, Nassau. |

(All photos and video by RJ Peltz-Steele CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.)

I was in Bahamas on the country's National Heroes Day on October 9. Bahamas replaced its Discovery Day, recognizing Christopher Columbus, with Heroes Day in 2013. The idea is to honor homegrown Bahamian heroes and shed the cultural domination of the islands' colonial past.

I've written before on my conflicted feelings about Columbus Day. So I was curious when my Lonely Planet told me that I would find a Columbus statue presiding over the capital at Government House in Nassau. Indeed, my pre-pandemic Planet was outdated. The statue was vandalized just in advance of Heroes Day in 2021 and moved into storage in October 2022.

I've written before on my conflicted feelings about Columbus Day. So I was curious when my Lonely Planet told me that I would find a Columbus statue presiding over the capital at Government House in Nassau. Indeed, my pre-pandemic Planet was outdated. The statue was vandalized just in advance of Heroes Day in 2021 and moved into storage in October 2022.

I found not only an empty pedestal with a crumbling top, but closed gates at Government House. Neglected surroundings, outside the gates, unfortunately spoke to my overall impression of economic development in the Bahamas.

|

| Two bridges connect Nassau to Paradise Island. |

|

| K9 Harbour Island Green School subsidizes most students' tuition. |

|

| A Disney ship departs Nassau before dusk. |

I wondered what shop workers on Paradise Island think when they leave the artificiality of the plaster-and-paint retail village, with its Ben & Jerry's and Kay's Fine Jewelry, for dilapidated, rat-infested residential buildings in the city's corners. I wondered whether tourists see the contrast when they are whisked through downtown en route from the airport to Paradise.

The heart of the city undergoes an equally striking transformation almost daily. Cruise ships pull into the port and unleash a legion of passengers into the downtown district. Western stores such as Starbucks and Havianas open up alongside overpriced jewelers and T-shirt purveyors.

(Video below: A funeral procession for Obie Wilchombe, Parliamentarian, cabinet minister, and tourism executive, proceeded through the heart of the tourist district while cruise passengers were in port on October 11. I watched, I admit, from the balcony at Starbucks. Tourists who didn't see the coffin must be forgiven for assuming the lively music signified joyful festivity. Embodiment of the tourism-government complex himself, Wilchombe likely would have approved.)

|

| Bahamas declared independence from Britain in 1973. |

|

| A night street party in Nassau reverberates. |

|

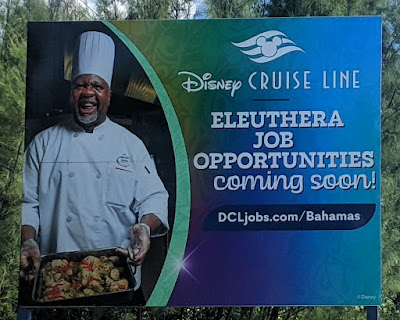

| Signs all over Eleuthera Island promise happy Disney jobs to come. |

The International Trade Association (ITA) well described what I saw: "The World Bank recognizes The Bahamas as a high-income, developed

country with a GDP per capita of $25,194 (2020) and a Gross National

Income per capita of $26,070 (2020). However, the designation belies

the country’s extreme income inequality, as statistics are driven by a

small percentage of high-net-worth individuals, while most Bahamians

earn far less." The only evidence of infrastructure investment I saw was that which directly benefited tourists and expats.

True to form, on a ferry between Eleuthera and Harbour Island, I overheard a couple of Americans in golf outfits discussing the plusses and minuses of potential investment in an island hotel. They seemed oblivious to the fact that the hotel name they bandied about was sewn into the breast of the short-sleeve work shirt of a local commuter sitting right beside them.

| |

| The historic "British Colonial" hotel, Nassau, lost its Hilton affiliation, but is under renovation with plans to reopen under independent operation. | |

Perhaps naively, I expected to find the Bahamas more a reflection of the western sphere of influence than of the developing world. It's only a 30-minute flight from Miami to Bahamas, and 85% of imports come from the United States. But on the ground on New Providence and Eleuthera Islands, the Bahamas reminded me less of Florida and more of Guinea-Bissau—a country plunged into darkness last week for failure to pay a $17m debt to its exclusive power provider, the offshore ship of a Turkish corporation.

Two years since Columbus was vandalized and one year since he was packed away, the solution to native identity at Government House is a rubble-topped pedestal and closed grounds. The people outside the gates have embraced National Heroes Day. But there is little information in circulation about who the Bahamian heroes are or why they should be celebrated.The government owes its people better. And I wouldn't mind seeing American- and British-owned tourism companies taking some corporate social responsibility—if that's still a thing—to ensure that something of what they pay into the country is reaching the people and lands that truly give life to today's Bahamas.

,_AD_160-180,_bronze_-_Worcester_Art_Museum_-_IMG_7704.JPG)