Two-volume TORTZ is free to download at SSRN: volume 1 and volume 2.

The books can be purchased in well bound, paperback hardcopy, both volumes for about US$61 plus shipping, from Lulu.com. The price is cost in the United States and just a couple dollars more elsewhere in the world.

Revisions in the 2025 edition include:

Premises Liability

- Discussion of Varley v. Walther (Mass. App. Ct. 2025) on "open and obvious" dangers in premises liability.

Product Liability

- Discussion of Amazon's product liability exposure, including the 2025 order of the Consumer Product Safety Commission.

- Discussion of the Texas two-step, including its rejection In re LTL Mgmt., LLC (3d Cir. 2023), and Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse's (D-R.I.) bill, the Ending Corporate Bankruptcy Abuse Act.

Life and Death

- Revised explanation and distinction of "wrongful birth," "wrongful life," and "wrongful conception" actions.

- Discussion of the waning "suicide rule" in the context of the wrongful

death suit by the family of Boeing whistleblower John M. Barnett in Stokes v. Boeing (D.S.C. 2025).

Government Immunity

- Discussion of Justice Clarence Thomas's displeasure with the Feres doctrine, dissenting from denial of certiorari in Carter v. United States (U.S. 2025).

- Discussion of 17 plaintiff families' victory in the bellwether Pearl Harbor-Hickam AFB water contamination trial, in Feindt v. United States (D. Haw. 2025).

Public Nuisance

- Note of Trumbull County v. Purdue Pharma (Ohio 2024), according with Okla. v. Johnson & Johnson (Okla. 2021), on opioids and product liability, excerpted in the book.

- Note of the Virgin Islands public nuisance lawsuit against Coca-Cola and Pepsico over single-use plastics, Commissioner v. Pepsico (V.I. Super. Ct. filed 2025).

- Note of Oklahoma's dismissal of a public nuisance claim over the Tulsa Race Massacre in Randle v. Tulsa (Okla. 2024).

Media Torts

- Discussion of the latest developments and Rule 11 sanctions in the battery and defamation litigation between promoters and rapper DaBaby, pending appeal from Carey v. Kirk (S.D. Fla. 2025).

- Update on impeached South African Judge John Hlophe's vendetta against former High Court colleague Judge Patricia Goliath, who innovated on anti-SLAPP in Mineral Sands Resources Ltd v. Reddell (High Ct. Wn. Cape Feb. 9, 2021) (upheld).

- Update on the enactment of revenge porn legislation in Massachusetts, the 49th state adopter, and the latest data protection bill in Massachusetts.

|

| 'DaBaby' Jonathan Kirk HOTSPOTATL via Wikimedia CC BY 3.0 |

- Discussion of the expansion of civil RICO by the Supreme Court in Medical Marijuana v. Horn (U.S. 2025).

Civil Rights

- Discussion of the landmark decision in climate change litigation in Europe, VKSS v. Switzerland (Eur. Ct. Hum. Rts. 2024), in contrast with the dismissal of Juliana v. United States (9th Cir. 2024).

- Note of the plaintiff victory in the Abu Grahib torture case, Al Shamari v. CACI (E.D. Va. 2024).

- Update on the real-life "Hotel Rwanda" protagonist's lawsuits against Rwanda and GainJet, the former defendant dismissed, Rusesabagina v. Rwanda (D.D.C. 2023), and the latter case, Rusesabagina v. GainJet (W.D. Tex. 2024), now pending appeal.

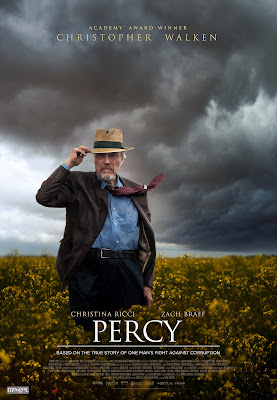

New Resources

- References to new audiovisual productions related to tort law and cases, such as "What Happened to Karen Silkwood?" on Impact x Nightline (2024); the latest on table saws from NPR: Planet Money (2024); Nicole Piasecki's "Dear Alice" from This American Life (2024); the documentaries Downfall: The Case Against Boeing (2022), and Youth v Gov (2020) (re Juliana v. United States), both now available on Netflix.

- References to recently published work on tort law and theory by Ken Abraham & Catherine Sharkey; Andrew Ackley; Christopher Ewell, Oona A. Hathaway, & Ellen Nohle; Dov Fox & Jill Wieber Lens; Kate Falconer, Kit Barker, & Andrew Fell; Jayden Houghton; Michael Law-Smith; Anatoliy Lytvynenko; Michael Pressman; Joseph Ranney; and Sarah Swan.

As in past editions, the coverage includes all of the fundamentals of common law tort, as well as full introductory treatments of

- defamation,

- privacy,

- interference, and

- private and public nuisance,

and introductions to

- business torts,

- the Federal Tort Claims Act,

- 'constitutional tort,' and

- worker compensation and alternative compensation systems.

Printed in color, Tortz is replete with

- 'RED BOX' treatments of fundamental rules to help students prepare for the bar exam,

- 'BLUE BOX' bibliographies of suggested further readings,

- 'YELLOW BOX' assignments to online readings and audiovisual materials, and

- 'GRAY BOX' state differences for Massachusetts bar candidates, or as demonstrative.

.jpg)